Looking for a good book? Who isn’t? It’s an eternal quest, but luckily one that’s not hard to fulfill. I hope you’ll find a few in this list of books I read in 2023.

Fiction

The All of It by Jeanette Haien

In this closely observed Irish novel, a newly widowed woman tells her village priest the long-hidden truth of her marriage and history.

American Ending by Mary Kay Zuravleff

As a reader, I love to feel I am in the good hands of a skilled author. That happened on page 1 of this novel about Yelena, the first American-born daughter in a family of Old Believer (essentially fundamentalist) Russians who were recruited to a coal town in Pennsylvania to work the mines. Yelena is American enough to want more from life than the domestic drudgery her family expects, taking her out of elementary school to care for younger siblings. Through her sharp observation and lively narration we watch Yelena’s family and neighbors struggle to honor their culture and claim the promise of America despite the abundant evidence that the country that beckoned them to its soot-smeared valleys does not much care if they survive.

Birnham Wood by Eleanor Catton

The book seems to start out as one kind of novel—a smart exploration of the friendship between two women and the personal dynamics of a left-wing organization—and unfolds into a shocking thriller. In New Zealand, Birnham Wood is a collective of “guerilla gardeners” who plant on neglected land that doesn’t belong to them and distribute their harvests to the hungry. The organization’s leader covets a large piece of unused land owned by a wealthy family, where her group could surreptitiously grow a bountiful harvest, except that an American billionaire also wants to use the land for his own secretive purposes. This is a novel that keeps you up late and troubles your sleep.

Brotherless Night: A Novel by V. V. Ganeshananthan

Powerful and moving story about a young Tamil woman, growing up in Sri Lanka in the 1980s, who expects to follow her four brothers by studying for a career in medicine or engineering. Instead, her world is upended by civil war and her family atomized in unimaginable ways. Even as she studies furiously in medical school, she is pulled into the war and its factions. Every decision, small and large—from which route to take home from school to whether to serve as a medic for the militant Tamil Tigers—demands an instant analysis of politics and risk. Are her friends and brothers terrorists? Victims? Both? A brilliant portrayal of what happens with history blows violently through people’s everyday lives.

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr

This novel has so many moving pieces that it’s hard to describe. Doerr tells five different tales from varied epochs and parts of the world, ranging from the experiences of a Greek oxen-handler in the 1400s to patrons of a public library in present-day Idaho to a young girl embarked on a lifelong space voyage in the future—all woven together by a particular ancient book and the love of stories in general. I didn’t expect to enjoy this book but ended up loving it. (Recommended by Janet Coleman.)

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

Stunning novel about a boy growing up in Appalachia amidst the poverty, addiction, and disinvestment endemic to the region. Kingsolver’s Pulitzer Prize-winning transformation of Dicken’s David Copperfield into modern-day America is a tour de force of narrative voice.

The Diamond Eye by Kate Quinn

Well-researched novel about a Russian woman who was seeking her Ph.D. when WWII broke out and she decided to join the army. She became an expert sniper, feared by the Germans and later feted by Eleanor Roosevelt in the U.S. The two women became friends and lifelong correspondents (historical fact), thanks in part to the fact that the Russian woman foiled an assassination plot against FDR (fiction). Now I know how snipers, who must hide for hours without moving, take their tea.

The Door by Magda Szabó

A writer in post-WWII Hungary hired a housekeeper to free up herself and her husband to attend to their newly ascendant writing careers. The housekeeper, Emerence, is a neighborhood luminary who insists on having a hand in every aspect of the writer’s home but keeps her own life off limits to all. Over 20 years their relationship morphs into a kind of intimacy and interdependence, until personal and cultural crises break the two women apart along the faultlines of class and history they had managed, at least temporarily, to transcend.

The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated by Susan Bernofsky

The novel illuminates the life and death—and various possible deaths—of an Austrian girl who grows into adulthood and age buffeted by the gales of 20th century European history. From provincial Austria, where her father was beaten to death by neighbors for the crime of being Jewish, to a poverty-stricken street in Vienna, to Stalin’s USSR where her left-wing politics are tested, to East Germany, we follow her through her many possible lives and endings. (Recommended by Kristin Ohlson.)

Enter Ghost by Isabella Hamad

Sonia Nasir is a Palestinian actress in her late 30s who has spent most of her life in London except for childhood summers living with family in Haifa. She has rarely visited the West Bank where most Palestinians live, and friends in England don’t even realize she’s Palestinian. But after a heartbreak she goes to stay with her older, politically active sister in Haifa, and ends up playing Gertrude in an Arabic production of Hamlet in the West Bank. Through the weeks of rehearsal she uncovers layers of meaning in the play for the Palestinian actors as well as secrets in her own family and political history—some that have been kept from her and some that she has kept from herself. As the performance date nears, demonstrations break out, the Israeli army targets the play as a security threat, and in that electric air Sonia finds herself fully awake at last to the revolutionary power of art and identity.

Exit by Belinda Bauer

A warm and surprisingly feel-good novel about death, dying, and the power of human connection. A 75-year-old widower named Felix belongs to an organization that serves as supportive witnesses to terminally ill people who take their own lives. One afternoon he brings a new, young volunteer with him on an assignment. Everything goes as planned, except that they realize as they leave the house that they have “exited” the wrong person. The plot spirals out to encompass and link Felix, his neighbor, the family of the mistaken exiteer, the volunteer trainee, the murderer, the police investigating the death, and the man who originally called for Felix’s services as he sought a dignified way out of life.

Fortune Favors the Dead by Stephen Spotswood

A fun, queer-infused mystery that takes place in 1940s New York City and features two women detectives: a brilliant, middle-aged woman who wears elegantly tailored men’s suits and is famous as the city’s leading “lady detective,” and her mentee, a younger woman who narrates the novel and who brings to her investigations skills from years working at a circus. This book is the first in a series, but while I enjoyed it, I think one will be enough for me.

Foster by Claire Keegan

Sharp, moving, brief story of the summer when a young Irish girl is taken in by distant relatives as her mother prepares to give birth to another child in an already large family. The girl’s parents struggle financially, with the father gambling and losing the family’s livestock and lying about harvesting crops that still lie rotting in the field. The couple who take her in are kind and loving, showing the girl small generosities she has never known, such as the man slowing his steps to match her own pace. The book is narrated by the observant young girl, with the same austerity and lack of sentimentality that shape her daily life at home.

Good Behaviour by Molly Keane

You know that feeling when something is both ghastly and funny, and you know you shouldn’t laugh but you can’t help it? That feeling suffuses this novel, which begins in post WWI Ireland with a murder of sorts and goes back to explain how the murderer got to this point. She is the best kind of unreliable narrator, so repressed and clueless that she has no idea how much she is revealing to the reader.

A Haunting on the Hill by Elizabeth Hand

A modern take on Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House—authorized by Jackson’s estate—this novel builds on the history of Hill House to create a fresh sense of intrigue, mystery, and dread. Holly is a playwright who’s received a small grant to work on her play, a feminist retelling of a woman’s execution for witchcraft. Desperate for the space to create and rehearse that’s unavailable in New York City, she rents for two weeks a crumbling, vacant mansion from a reluctant owner, and brings together her crew: her girlfriend, a talented singer; a friend who’s an actor and sound engineer; and a once-famous actress sidelined by a mysterious accident. They all have their secrets and so does the house, which brings out the creative best and the terrifying worst from the troupe and the townspeople. I listened to this as an audiobook, which I don’t recommend. They added silly and distracting sound effects to a narrative in which Hand’s words created all the chills any reader needs.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano

A vibrant novel about four sisters who grow up in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago and expect that, like their family and neighbors, they will all live within walking distance of each other forever, fulfilling their destiny in predictable ways. Life, of course, has different ideas, including the divorce of the oldest sister from her reserved husband, unexpected love affairs, an unplanned pregnancy, the death and distancing of parents, and a young woman, raised in isolation from the family embrace, who defies her mother to find out where exactly she belongs. I enjoyed and admired the novel but was struck by its weird timelessness. For example, part of the book takes place in 2008, but none of the characters seem to notice that the first Black president, from their own city, is about to be elected.

The Hours Count by Jillian Cantor

I read biographies of Lorraine Hansberry and Sylvia Plath, both of which discussed the powerful impact the execution of the Rosenbergs had on the writers. It inspired me to read this novel, which focuses on the life of Ethel Rosenberg as a young mother who has put aside her socialist activism—common among New York’s working class Jewish community—to focus on raising her children. Ethel makes friends with a neighbor in their New York apartment building, also a young Jewish mother, who is not as intellectual or political as the Rosenbergs. The narrator takes a long time to wake up to the dynamics that are swirling all around her as the nation’s anti-communist crusade brings its blades closer and closer to her friend and her own family.

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai

The ever-reliable Rebecca Makkai explores the social glamor of violence against women and the permeability of truth and memory in this latest novel. Bodie Kane, a film studies expert and podcaster, returns to her alma mater, a fancy New Hampshire boarding school, to teach a winter seminar. One of her students decides to—or did Bodie nudge her into it?—investigate the murder of a female student that took place on campus 25 years ago. The victim was Bodie’s roommate. The novel is partially a murder mystery and largely an examination of what people notice and remember, and how they shape reality through the stories they tell each other and themselves. Bodie’s narrative voice is distinctive and unforgettable, a work of art.

Jackie and Me by Louis Bayard

When the young Congressman Jack Kennedy gets engaged to the even younger Jacqueline Bouvier, he recruits his best friend, a gay man, to squire Jackie around town and keep her occupied while Jack lives his life as he always has and always intends to. A bittersweet and enjoyable novel, particularly for those who lived through the Kennedy era.

Lakewood by Megan Giddings

A young Black woman, desperate for money and health insurance for her mother, takes a job as a test subject in a long-term research project conducted in a remote town by a secretive government entity. The researchers are white; the subjects, who must sign NDAs and lie to everyone about where they are and what they’re doing, are people of color and a few working-class white people. The research appears nonsensical and increasingly torturous. As the reality of her situation dawns on the young woman, the double-edged knife of horror and political recognition cuts ever deeper for the reader. This is Giddings’ first novel, and the growth of her narrative control is evident in her excellent next book, The Women Could Fly.

The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell

The story of a young noblewoman in 16th century Italy, a woman too brilliant and fiery for her times, who realizes her husband is planning to murder her. A well-written soap opera with a disappointing ending.

Moonrise Over New Jessup by Jamila Minnicks

A young Black woman fleeing north from Jim Crow stumbles upon the miraculous all-Black town of New Jessup, Alabama. She stays, falls in love with the town and its people, and marries one of its long-time residents. She and her family face rising tension as the unyielding racism of the county surrounding New Jessup and the civil rights movement with its call for integration press in against a town already crackling with conflict between the older and younger generations and their dueling visions for the future. I loved this book so much I did not want it to end.

Night Wherever We Go by Tracey Rose Peyton

Six enslaved women on a Texas plantation conspire with and sometimes chafe against one another as they fight to claim what little autonomy they can from “the Lucys,” the married couple who enslave them and are clearly the spawn of Lucifer. In particular, the women use their strength, skills, and wiles to avoid being bred like animals in order to create children who will constitute more property for the Lucys to profit from. A powerfully written dark novel lightened only by glimmers of hope.

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield

Haunting novel about a woman whose wife, a marine biologist, goes on a disastrous deep-sea voyage and comes home utterly changed. The book moves with an underwater languor and strangeness as it explores the slow-motion horror of losing the people we love even as we hold them close.

The Pale Blue Eye by Louis Bayard

An unusual meld of historical fiction and literary murder mystery that takes place in 1831 at West Point Military Academy. A cadet has been found hanging, and when somebody steals the body, officers turn for help to a retired police detective with a tragic past who lives nearby. He investigates the mystery—and a string of related deaths and disappearances—with the help of an unlikely cadet, a poet named Edgar Allen Poe. Moody and atmospheric, filled with descriptions of winter in the “highlands” of West Point, the novel delivers finely drawn characterizations of the male characters (the few female characters are much less robust) and startling plot twists.

Shrines of Gaiety: A Novel by Kate Atkinson

A spirited romp through post WWI London, with a focus on the seamy side: gangsters, scammers, detectives, nightclub owners and customers, and one librarian determined to solve the mystery of two missing girls and grab a taste of life while she’s at it. Unlike most stories about missing girls, in this one readers knows where the girls are and what they’re up to. We are just along for the ride to enjoy careening through the world Atkinson creates.

Stolen by Ann-Helén Laestadius

This fascinating novel begins with a murder—of a reindeer, the livelihood and cultural heart among the indigenous Sámi of the Arctic Circle. A young Sámi girl witnesses the killing, done by a brutal and powerful Swedish (think: white) man from the nearby village, but doesn’t dare to name him. As she grows up, seeing more and more reindeer killings that the police dismiss as nuisance thefts but the Sámi consider hate crimes, she becomes more deeply aware of her community’s precarious position in the wider Swedish society and grows into an advocate. The book is the author’s first novel for adults and reads like it, but it doesn’t shy away from examining the systemic discrimination against the Sámi or the sexism within the Sámi society that keeps women oppressed and the community unequipped for the future.

Thank You, Mr. Nixon by Gish Jen

Short stories about Chinese people in America, their American-born children in China and the U.S., and their wildly varied experiences of what it means to have, lose, or long for a homeland. I am not the first to notice: Gish Jen can write.

Time’s Undoing by Cheryl A. Head

In 2019 a Black journalist for the Detroit Free Press whose beat is the Black Lives Matter movement goes to Birmingham, Alabama to research the life and death of her great-grandfather. Her family believes—but doesn’t know for sure—that he was murdered by police in 1929. In Birmingham, she befriends a city official and a local activist who introduce her to the best and most bitter of the city’s Black culture and history, and a white librarian with dazzling research skills and family connections that reach back decades. But not everyone supports the journalist’s investigation into a police murder of a Black man, even one that took place 90 years ago. She must figure out who still wants to hide the truth, and why—and how far they’ll go to keep the secret.

The Travelers by Regina Porter

I loved this complex, captivating novel about two sprawling families, one Black and one white, from Buckner County, Georgia, and the Bronx. The novel spans from about 1950 to 2010, in locations that range from a police car in rural Georgia to a street corner in Los Angeles to an apartment in the Bronx to a ship in Vietnam and more. While the characters and storylines intersect, each character is crisp, clear, and fully alive. An engrossing read and an impressive feat of storytelling and narrative structure.

The Trees by Percival Everett

Hard to know how to describe this novel, which is at once a thriller, a comedy, a ghost story, a revenge plot, and a farce about, of all things, lynching. The novel begins with the murder of two white men in Money, Mississippi, where Emmett Till was slaughtered, and the culprit appears to be a Black man, himself dead, who resembles Till. Stir in more murders of white racists by apparently dead Black men, some witty Black FBI agents, clownishly stupid white officials, an astounding research project and a mysterious training program, both led by a 105-year-old root woman, and you have a story that strikes the reader’s nerves on all levels, from laughter to horror. I ended up not knowing how to feel about the book—but I haven’t stopped thinking about it.

Upright Women Wanted by Sarah Gailey

A young woman named Esther appears to live in the Old West. But in fact it’s the U.S. of the near future, in which white and male supremacy rule, electricity and technology exist only for the elite and the military, and Esther has just witnessed the public hanging of her lover, Beatriz, for “deviance.” She hides herself in the wagon of some Librarians, a select cadre of “upright women” who are allowed to travel the countryside by horse and cart to bring books—government-approved propaganda—to rural dwellers. Esther soon discovers that the Librarians are more radical than they appear. They risk much more than snakebite and bandits to deliver books and a glimmer of liberation to women like themselves and like Esther, who strives to earn her way into their ranks.

Yellowface by R.F. Kaung

In this entertaining satire about the publishing world, a young white writer named June, who is our narrator, has a love-hate relationship with a much more successful Asian writer named Athena. When Athena dies (horribly) in front of June, the narrator steals her unpublished manuscript, which is about the WWI-era Chinese Labor Corps. Nonetheless, she submits the manuscript as her own. It becomes a best seller, vaulting June into the literary stratosphere her dead friend used to inhabit, albeit one peppered with prickly questions about cultural appropriation and why Athena’s ghost keeps appearing at June’s public events in her social media.

Nonfiction

The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church by Rachel L. Swarns

In an astonishing feat of archival research and narrative, Swarns unveils the history of how Georgetown University and the Jesuits who founded it financed their activities and livelihoods—through the forced labor of enslaved people they “owned,” working in the fields and houses of several plantations the Catholic church owned in Maryland. When attendance at the new Georgetown University faltered, the Jesuits chose to make up the shortfall by breaking up enslaved families and selling people into more brutal and arduous servitude in Louisiana, including a family who had served the Jesuits so loyally and so long that the priests promised never to sell them—but did so anyway. (Recommended by George Walker.)

Cheap Land Colorado: Off-Gridders at America’s Edge by Ted Conover

Conover went to the desolate, nearly empty flats of southern Colorado to get to know the people who moved there for the cheap land and abundant isolation. He ended up loving the place and appreciating many of its people—even the racist, gun-toting, Trumpian ones—and buying land himself, where he lived part-time. The rest of the time he lived with his wife in NYC, where he taught in the NYU grad school. Quite a contrast. I was intrigued by the stories of what prompted people to move to this part of the country, and of their intrepid strategies to keep themselves warm and fed in a place with no infrastructure. But Conover’s ability to melt into their world struck me as nothing to envy.

City of Refugees: The Story of Three Newcomers Who Breathed Life into a Dying American Town by Susan Hartman

Wonderfully vivid and intimate portrait of the Rust Belt city of Utica, New York, which had lost large percentages of its population, not to mention its vitality and hope for the future, until it began to welcome refugees. Hartman takes us deeply into the lives of three refugees—from Somalia, Iraq, and Bosnia—and their families, their struggles and joys, and their immense creativity and industriousness as they come to terms with the traumas they’ve endured and make a new life for themselves in America. The author went to college with me, although I didn’t know her, and throws a new and fascinating light on the city closest to our campus.

A Dangerously High Threshold for Pain by Imani Perry

Do yourself a favor and read everything Imani Perry writes. In this long audiobook essay, she examines the world of chronic pain and illness, which she officially joined when she received a diagnosis of lupus after years of misdiagnosis as well as patronizing and racist treatment from doctors. Perry doesn’t treat herself much better, ignoring her pain as she pursues punishingly difficult academic, professional, and personal goals. Over the years, she learns to extend to herself and her body the compassions she deserves, but it’s a rough journey.

Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Naomi Wolf is a formerly feminist writer who became a right-wing fanatic and regularly appeared on Steve Bannon’s podcasts to rail against Covid vaccinations she claimed were turning people into non-human slaves. What she is not is Naomi Klein, a leftist writer whose subject is the ravages of capitalism, and the author of this illuminating book. But when Klein finds herself consistently confused with Wolf on social media and elsewhere, she spends the long days of Covid isolation delving into Wolf’s milieu. What she discovers is a “shadow world” in which far-right figures, led by Bannon, strategically turn progressive messaging inside out to create a political home for people who feel left behind by movements such as Black Lives Matter and the environmental movement. Klein highlights the white women influencers who co-opted the principle of “My body, my choice” from a demand for reproductive justice to a refusal to wear a mask or get a shot in order to keep other people safe. She brilliantly reveals that the bizarre conspiracy theories of the far right, which have gained such surprising traction, have direct corollaries in the real-life conspiracies we rarely discuss but that shape our daily lives, such as capitalism and white and male supremacy.

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History by S.C. Gwynne

In 1836, a nine-year-old white girl whose family had built a compound in the Indian territory of Texas was kidnapped by Comanches. She grew up in the tribe, married, had children, and when she was “rescued” by Texas Rangers in 1860, spent the rest of her life trying to get back to the Comanches. Her son Quanah is the central figure in this sweeping story of American history, warfare, genocide, cultural erasure, and the world-changing power of new technologies, from the horse to the revolver to the railroad. The book was written in 2010 and has some cringe-worthy blind spots—for instance, the author looks to Nazi Germany rather than to U.S. slavery and Jim Crow for examples of officially sanctioned cruelty—but it still throws light on the consequential era in which Indigenous tribes dominated the West and its white settlers but then were pushed close to annihilation.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell

Lovely but harrowing memoir of travel, coming of age, motherhood, perils avoided and survived, health crises and the callousness of health care systems, and the evolution of a writer’s mind and artistry. (Recommended by Melissa Middleman Firman.)

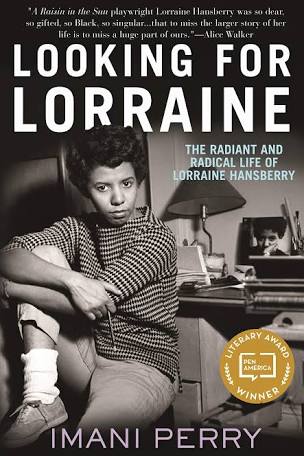

Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry by Imani Perry

Excellent biography of the writer best known for “A Raisin in the Sun,” the first play written by a Black woman to be produced on Broadway. Perry explores Hansberry’s wide-ranging writing, her lesbian life, her commitment to left-wing activism, her intense artistic and political friendships with people such as Nina Simone and James Baldwin, and her struggles with the FBI, writer’s block, and eventually cancer. I found myself in tears at the end of the book, when Hansberry died at age 34 (in 1965), because Perry’s work made me feel I had lost a friend and a comrade.

The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World by Sarah Stewart Johnson

I love books like this in which the writer reveals the romance in a subject that otherwise holds little interest for me. The author is a planetary scientist who has a lifelong obsession with Mars and, as a teenager, found that pure math was a language that “opened up the world” to her. In accessible and often lyrical language, she examines the history of Mars exploration, from the earliest sightings in a primitive telescope to the most recent data transmitted from the planet’s surface by various Mars landers, and illuminates how science has informed our changing understanding of the nature of life and our own planet. Throughout the narrative, Stewart Johnson weaves in stories of her own experiences, as a student and later a scientist and professor who worked on several of NASA’s Mars missions.

The Six: The Untold Story of America’s First Women Astronauts by Loren Grush

Interesting behind-the-scenes look at the recruitment, training, and experiences of the first American women astronauts to fly into space, not all of whom returned to earth.

Sovietistan: A Journey Through Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan by Erika Fatland

Lively mix of travelogue, history, and cultural and political analysis of the five former Soviet states by an intrepid, multi-lingual Norwegian journalist who traveled these little-known countries on her own. I appreciated her observations about women’s lives and freedoms (or lack thereof), so often overlooked in other books.

This House of Sky by Ivan Doig

Beautifully written memoir of a way of life that was fading even as the writer lived it. After Doig’s mother died when he was six, he shared with his father the demanding and unpredictable life of a lamb rancher in the wide-open Montana of the 1940s and 1950s. They moved with the seasons and scraped by in whatever ramshackle accommodations the ranch owner provided. It was a hard and decent life but no way to raise a child, so Doig’s father eventually asked his former mother-in-law, Ivan’s grandmother, to move in with them to provide the boy some stability. Ivan lived with these two stalwart, down-to-earth people—although often he boarded with others during the school year because they ranches they worked were too remote—until he left for college and then graduate school. There he met modernity and realized that almost no one he encountered from now on would be familiar with the rustic Western life he had known. (Recommended by Elizabeth Marum.)

These Precious Days by Ann Patchett

A series of personal essays about the writing life, Patchett’s friends and family, the power of reading, illness and isolation, and what humans owe one another. Of course the essays are exquisitely crafted, since it’s Patchett, but the book as a whole is a little redundant, since many of the essays have been previously published as stand-alone pieces and were not intended to be read sequentially. (A gift from Susan Hester.)

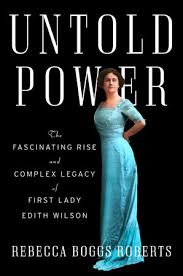

Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson by Rebecca Boggs Roberts

I had no intrinsic interest in Edith Wilson or her husband Woodrow, but the subtitle doesn’t lie: The book is fascinating. Edith was a widow and a successful businesswoman when she married Woodrow, who was already the president, and hoped he wouldn’t win reelection so they could enjoy a quiet life together. He did win, and she longed to be involved in policymaking, a role for which the First Lady had no authority. (Women couldn’t even vote yet, and Edith didn’t want them to.) When Woodrow had a stroke, Edith fully yet secretly acted in his stead, making her perhaps the most powerful First Lady ever—for good or ill.

The Wager and The Lost City of Z by David Grann

I’ve now read several books by Grann, trying to recapture the excellence of Killers of the Flower Moon, and that might be enough. He specializes in obsessively researched books about obsessed men. The Wager tells the story of a shipwreck and the terrible ordeal of the survivors, with the added twist that the survivors had split into factions that accused each other of mutiny and murder. Exasperated naval officials in England, who had thought all the seafarers dead, had to try to straighten out the conflicting stories when the survivors returned years later. In The Lost City of Z, a swashbuckling British explorer repeatedly and over many years treks through the Amazon jungle in search of an ancient city full of cultural treasures and gold. It is a journey so perilous his own son dies in the quest. Decades later, Grann tries to follow his trail.

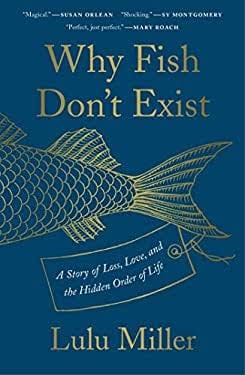

Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life by Lulu Miller

This is the rare book in which the author begins to write about a subject she admires—in this case, scientist and Stanford University’s first president David Starr Jordan—but the more she learns about him, the more horrified she becomes. Miller wraps her own personal story, about a man she can’t get over followed by a woman who feels like home, into the narrative about science, history, and the power of noticing that things are not as they appear.